Hydrogen has long been seen as a potential clean energy source. The challenge has been splitting water into hydrogen and oxygen through electrolysis, which requires large amounts of electricity. Even small efficiency improvements at scale can save millions of dollars and bring hydrogen closer to competing with fossil fuels.

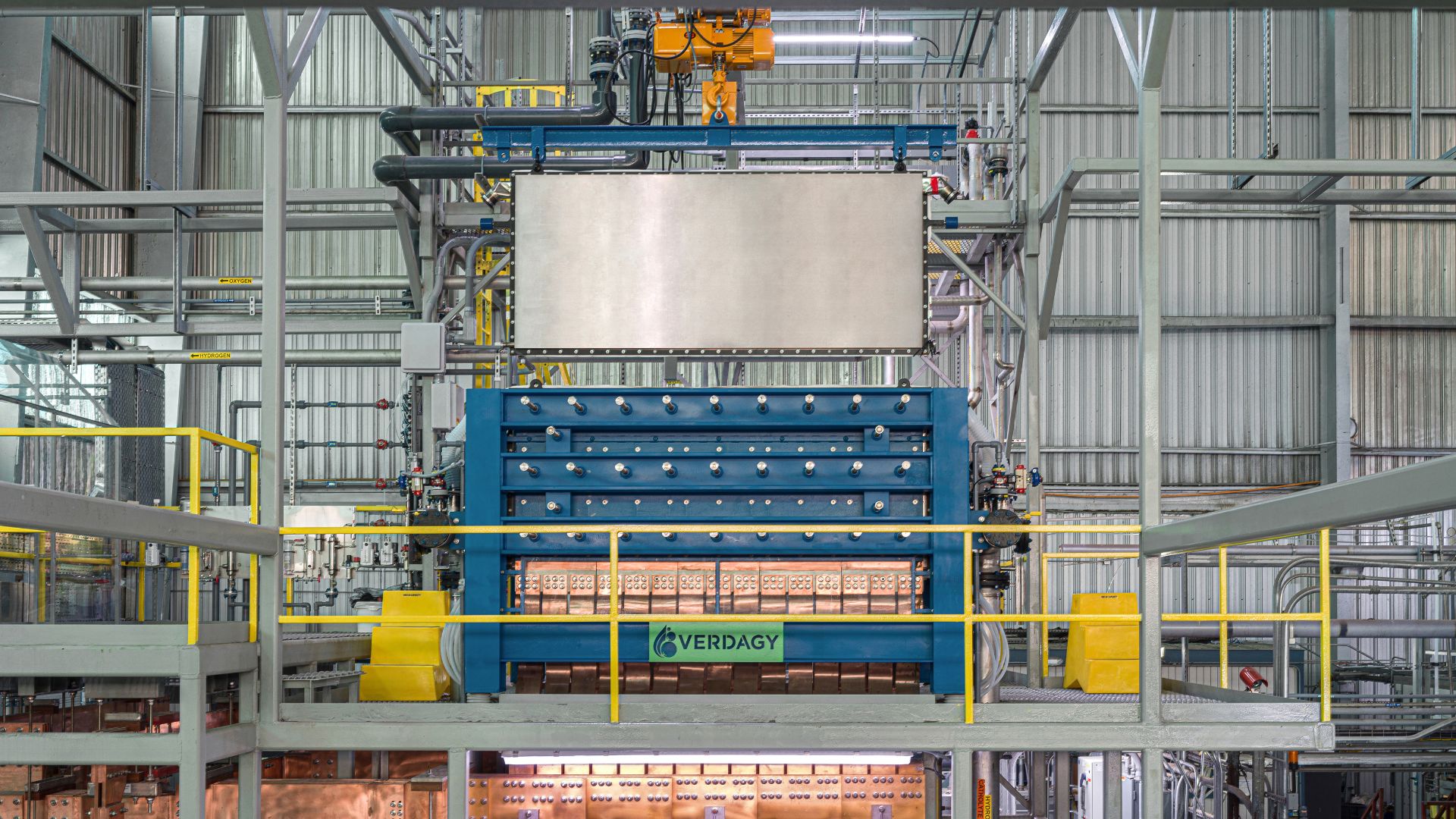

California-based Verdagy, which develops large-scale water electrolysis systems, claims its proprietary “Dynamic AWE” has set a new efficiency standard across the operating range of electrolysis, surpassing the US Department of Energy (DOE) targets years ahead of schedule.

The company says its results are based on strict benchmarking and a unique system design that diverges from much of the industry.

In an interview with Interesting Engineering, Dr. Kevin Cole, Verdagy’s Chief Technology Officer, spoke about how the company validated its efficiency claims, how those gains translate into real-world economics, and what it means for the global race to produce green hydrogen at $2 per kilogram, the milestone that governments and investors alike see as the threshold for fossil parity.

Benchmarking the unbenchmarkable

Electrolyzer companies rarely publish comparative data. Pressure, temperature, and stack design all affect performance, leaving firms free to highlight selective metrics. Cole said Verdagy wanted to avoid that trap.

“The performance of all systems was benchmarked to atmospheric pressure by calculating the compressive power needed to achieve different levels of compression,” Cole explained, referring to the Department of Energy’s long-running H2A model for hydrogen delivery.

Using published specifications from manufacturers’ white papers, typically operating pressures and hydrogen output levels, Verdagy calculated the compression power required, then normalized every system’s efficiency to atmospheric conditions.

“You don’t need to know the size of the stack,” Cole said. “Just by those two numbers in the equation, you can calculate the energy and then subtract it to normalize efficiency.”

This method excluded unknowns like shunt currents, which are abandoned electrical flows that bleed efficiency in traditional alkaline stacks, especially at low current densities.

“The influence of shunt currents in different systems is unknown and couldn’t be accounted for,” Cole acknowledged. “But with Verdagy’s single-cell architecture virtually eliminating shunt currents, the performance gains compared to competitors are likely even larger than plotted.”

Verdagy published a technical white paper, highlighting how mysterious electrical losses can drag down efficiency across a full-scale plant.

Why efficiency matters more than ever

Cole stressed that efficiency is not just an engineering trophy metric. It maps directly onto the economics of hydrogen production.

“With the improved efficiency of 1 kWh/kg at 1.6 A/cm², and say an electricity price of $50/MWh, this translates to a savings of $0.5/kg of hydrogen,” he said. At a 100-megawatt Verdagy plant, those half-dollar savings scale to $10,000 per day, or $3.65 million annually.

While $0.50/kg may not close the gap with fossil fuels alone, those marginal improvements accumulate in a world where the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) and the Department of Energy’s Hydrogen Shot initiative set a $2/kg cost target by 2030.

“A one kilowatt-hour per kilogram efficiency improvement is huge and meaningful,” Cole said.

Different markets prioritize different performance dimensions. Cole explained that in Western markets, where land is scarce and electricity expensive, efficiency and hydrogen yield per square foot dominate decision-making.

In regions with cheaper electricity, CapEx takes precedence. Across both contexts, the key concept Cole stressed was hydrogen accountability: the ability to reliably produce a specified daily output.

“Hydrogen is rarely used on its own,” he said. “It’s usually used downstream in other products, such as ammonia or e-fuels. Those processes count on hydrogen, and you design a plant around exactly how much you need per day. So accountability, not just efficiency or durability, ensures low-cost hydrogen delivery.”

Design trumps materials

One of Cole’s more provocative insights is that system design, not material science, currently dominates the efficiency frontier. Unlike lithium-ion batteries, where mature designs leave little room for differentiation beyond materials, electrolyzers still exhibit vast design divergence.

“I’ve seen scenarios where an electrode performs exceptionally well in electrolyzer A, and then electrolyzer B tries that same electrode, and it’s one of the worst ever tested,” Cole said. Gas transport dynamics, thermal management, and balance-of-plant design play an extreme role in efficiency.

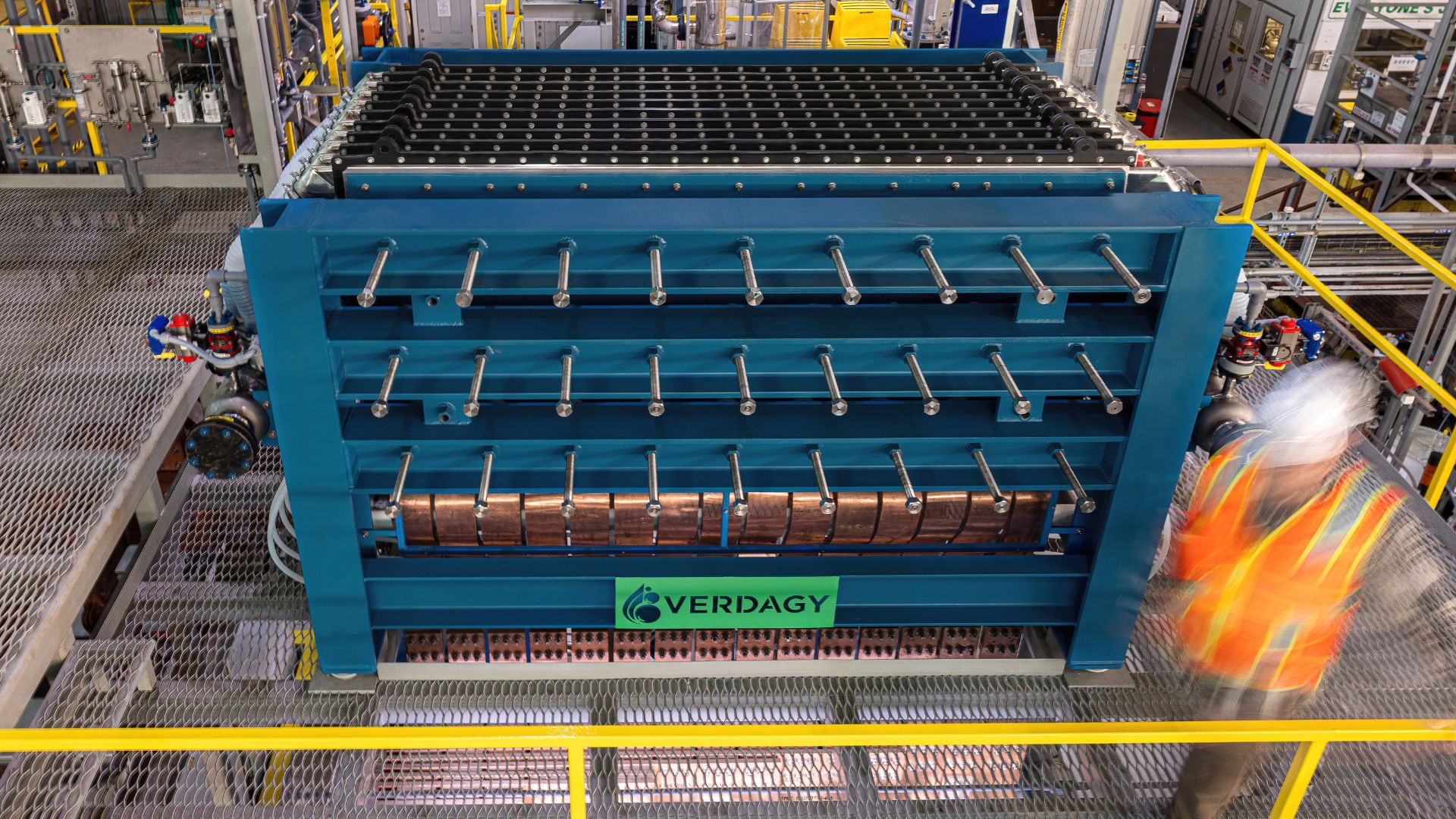

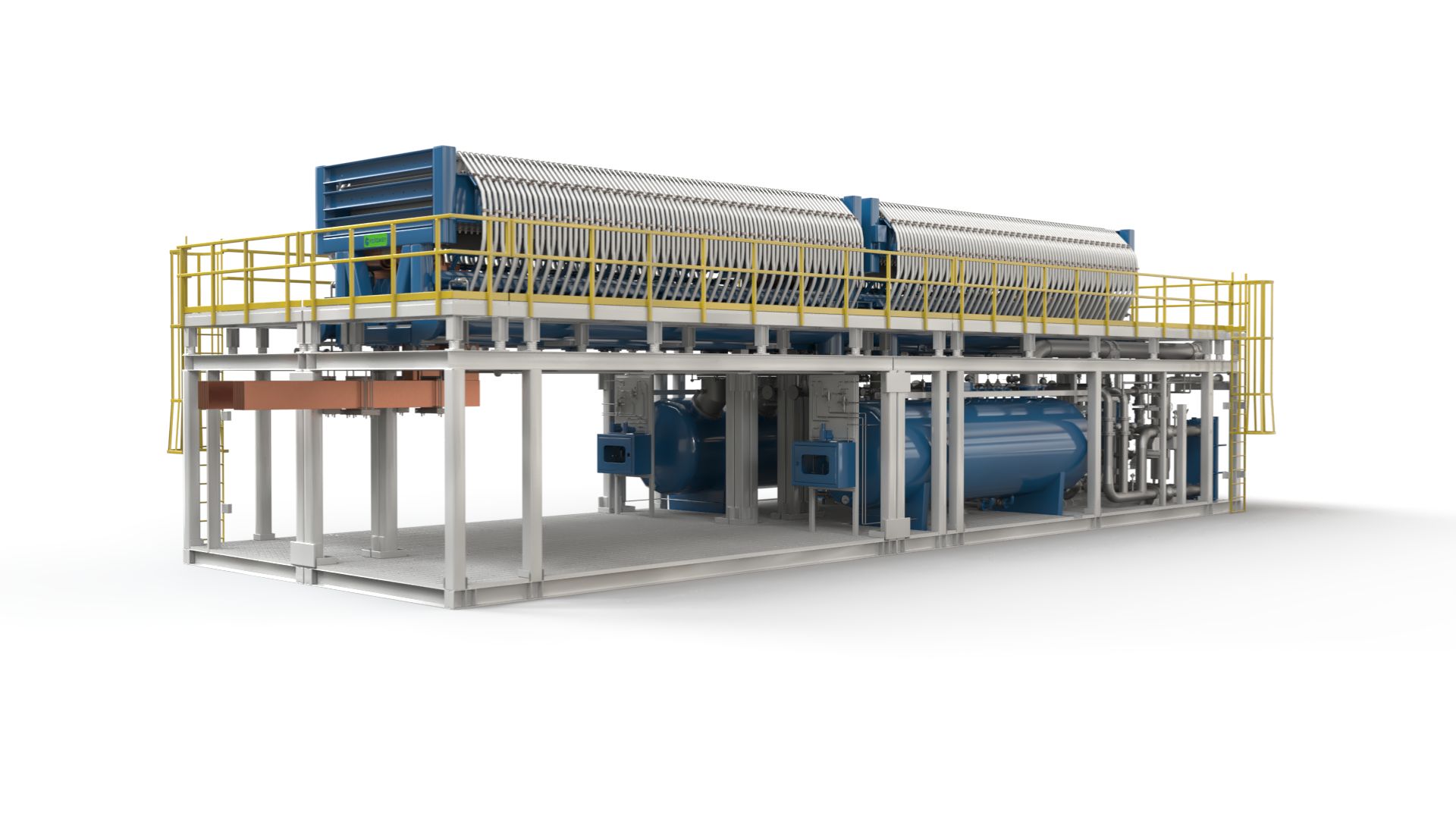

Verdagy’s system borrows heavily from chlor-alkali, a century-old industrial electrochemical method used worldwide for chlorine production. By adapting this architecture specifically for hydrogen, the company claims to have achieved the highest current density and turndown ratios in the alkaline category.

Verdagy’s single-cell architecture also upends conventional maintenance cycles. In a traditional multi-cell stack, degradation forces periodic wholesale replacement. Verdagy allows modules to be serviced in rotation, even while the plant runs.

“If you have a 100 MW plant with five 20 MW stacks, and overnight you only have 40 percent renewable power, you don’t have to run each module at 40 percent,” Cole explained. “You can run four at 50 percent, shut one down, and service it. The next night, you do the next one. You can maintain or even upgrade cells without ever stopping production.”

That flexibility dovetails with intermittent renewable inputs, making the system especially compatible with wind and solar.

The competitive landscape: AWE, PEM, AEM

Electrolyzers today can be categorized into three main families, each with unique characteristics and advantages.

The first group is proton exchange membrane (PEM) electrolyzers. These devices are known for their efficiency at baseline levels, making them an attractive option for various applications. However, their reliance on costly platinum-group metals for catalyst materials can make them a more expensive choice in the long run.

Next, anion exchange membrane (AEM) electrolyzers are considered promising newcomers in electrolysis technology. AEM electrolyzers could be a cheaper and more efficient option than traditional methods. However, they have issues with durability and stability during use.

Lastly, alkaline water electrolysis (AWE) has been a reliable workhorse in the industry. AWE systems are known for being affordable, making them a good choice for large-scale hydrogen production. However, these systems are less efficient at high current densities than PEM and AEM systems. Despite this limitation, AWE’s established presence in the industry keeps it an important option in the electrolyzer market.

Verdagy’s Dynamic AWE is pitched to retain alkaline’s durability and cost benefits while closing its efficiency gap with PEM.

Cole said most US and European players, including Nel, Plug Power, Cummins, and Thyssenkrupp, are focused on PEM. “There are very few actual competitors working on alkaline at the scale we are,” he noted. “We’ve taken chlor-alkali, one of the only industrially viable electrochemical processes, and modified it specifically for hydrogen.”

Both policy and market forces shape Verdagy’s position in the world. In Europe, there is a strong focus on high efficiency and using renewable energy. Companies like Nel and Thyssenkrupp work closely with EU rules to achieve sustainability goals.

On the other hand, China focuses on cutting costs by using large-scale production. This strategy helps Chinese companies lower prices and speed up the development of renewable technologies. Each region is developing its strengths based on specific goals and plans.

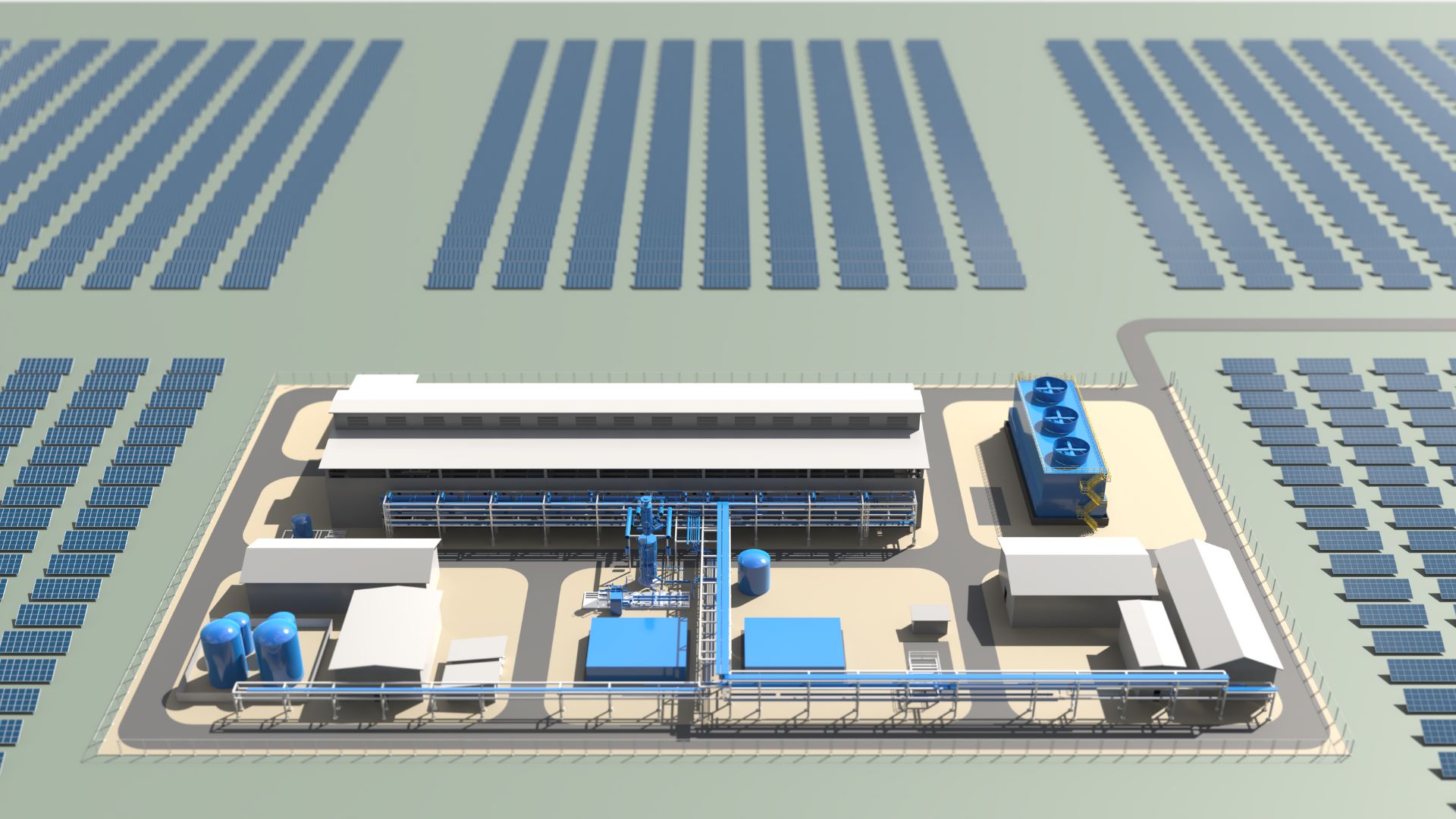

Verdagy is betting that its ability to operate at 1.6 A/cm² current density with wide turndown ratios positions it for both markets. High efficiency per square foot appeals to land-constrained Europe, while manufacturing scalability addresses China’s cost pressure.

“We developed and operated an advanced manufacturing facility designed for gigawatts of production capacity,” Cole said. “Together, Verdagy can compete in any market and deliver industry-best LCOH.”

Mapping to DOE and IRA targets

The DOE’s technical targets for alkaline electrolysis call for 48 kWh/kg at 1 A/cm² by 2026 and 45 kWh/kg at 2 A/cm² by 2030. According to Cole, Verdagy has already surpassed the 2026 benchmark and is now pushing into 2030 territory.

“Others believe they’ll get there by 2026, but as of today, Verdagy has already passed that threshold,” he said. The company aims to meet DOE’s technical goals and align with the IRA’s $2/kg cost target, a benchmark that would unlock subsidies and mass deployment.

When Verdagy announced it had set a “new efficiency standard across the operating range,” some observers dismissed it as hype. However, Cole’s detailed breakdown suggests the claim is grounded in normalized benchmarking, not cherry-picked lab numbers.

The company has also highlighted its ability to couple with renewables, its scalable manufacturing base, and its modular architecture as differentiators. In Cole’s telling, these are not buzzwords but deliberate design choices to tackle the bottlenecks that keep green hydrogen expensive.

Outlook

The history of hydrogen is full of overpromises. PEM has been slowed by scarce catalyst metals, and AEM still struggles with durability. Verdagy is betting that a reengineered alkaline platform, built on proven chlor-alkali chemistry but optimized for renewable grids, offers the fastest route to competitive costs.

Challenges remain: financing large deployments, proving long-term reliability, and securing certifications for multi-hundred-megawatt plants. Efficiency improvements are necessary but not sufficient.

For now, Verdagy’s benchmarks matter. By showing normalized efficiency translating into millions in annual savings at scale, and aligning with DOE and IRA targets, the company has positioned itself as a serious contender in the green hydrogen race.