Support CleanTechnica’s work through a Substack subscription or on Stripe.

In 2019, South Korea announced a program that was meant to make the country a global leader in hydrogen transportation. The government declared that all 802 police buses then in service would be replaced with hydrogen fuel cell models by 2028.

These were not ordinary buses. They were national security assets used to transport officers in large groups, often for crowd control or emergency deployments. They were highly visible symbols of state capacity. Outfitting them with hydrogen was intended to show that the country was serious about making hydrogen transportation the future. Hyundai delivered early prototypes, ministries set aside billions of won, and plans for hundreds of fueling stations were published. At the time, South Korea was among the few countries willing to put hydrogen into such a prominent operational role.

Six years later the reality is very different. By the end of 2025 only 16 hydrogen police buses will be in operation. More than $7.2 million has been spent, but the rest of the fleet has not materialized. The police have made their position clear. They will not buy more. The reason they gave is simple. There are not enough hydrogen fueling stations to keep the buses on the road reliably. Even though South Korea built dozens of stations, many have limited hours, ration fuel, or are out of service. For a fleet that must be ready to deploy at any time, this is unacceptable. The police decision is the practical end of the program.

Seen through Bruno Latour’s actor network theory (ANT), this moment matters because it exposes the way hydrogen transportation in South Korea had become a black box. The inscription was “hydrogen transportation is the future.” Once that story was inscribed it was treated as fact. Politicians, ministries, Hyundai, and provincial governments aligned behind it. Subsidies flowed and press conferences reinforced the message. In ANT terms, problematisation defined hydrogen as both an industrial strategy and a climate solution. Interessement brought in actors who had reasons to support the story. Mobilisation created surface stability through subsidies and pilot projects. But when the police looked inside the black box, what they found did not match the inscription. Costs were high, fueling was unreliable, and buses could not perform the role expected of them. By stepping away, the police enacted a betrayal in ANT terms. They were an obligatory passage point, and their refusal to reproduce the narrative weakens the network itself.

Inside the box the economics were never favorable. Hydrogen buses remain more expensive to buy and operate than battery electric ones. Stations cost millions to build, have low throughput, and break down often. Fuel is expensive compared to electricity. A bus that should be on the road may sit idle waiting for a tanker to deliver hydrogen or for a compressor to be repaired. The safety record has also raised concerns. The December 2024 explosion of a hydrogen bus in Chungju that injured several people underscored that even mature fueling equipment carries risks. These are not minor inconveniences. They go to the core of whether a fleet can function.

The decision of the police is one sign in a broader pattern. South Korea had ambitious hydrogen plans beyond the police buses. The country pledged to have more than 21,000 hydrogen buses on the road by 2030 and built industrial policies to support Hyundai’s fuel cell offerings. Yet actual uptake is faltering. The Hyundai Nexo, the country’s flagship fuel cell car, saw sales fall from more than 10,000 units in 2022 to fewer than 3,000 in 2024. While a redesigned Nexo and a hard push has increased sales in the first half of 2025, it’s unlikely to hit 10,000 this year. The infrastructure targets have slipped repeatedly. The number of fueling stations has lagged far behind projections, and many that exist have poor availability.

The global picture mirrors these struggles. Japan’s Toyota Mirai has never achieved more than niche sales. After a brief push in California, many of the state’s hydrogen car fueling stations are shutting down, leaving drivers stranded. European cities that experimented with hydrogen buses are shifting their procurement to battery electric fleets, citing lower costs and better uptime. Even in China, which has supported hydrogen trucks with subsidies, the numbers are small compared to the millions of battery electric vehicles being produced and sold each year. Hydrogen transportation is consistently failing in the market segments where it was once thought to have a role.

Battery electrics tell the opposite story. In South Korea BEV sales in 2025 are surging. In the first seven months alone, 118,717 were sold, nearly matching the entire 2024 total. In July sales grew 67% year over year, and BEVs are now more than 13% of new car sales. The infrastructure to support them is scaling quickly, costs are falling, and models are available across price ranges. Globally BEV adoption is accelerating in Europe, China, and North America, and in fact in every country in the world. The actor networks around battery electrics are strengthening with every quarter because what’s inside the black box actually works economically and reliably.

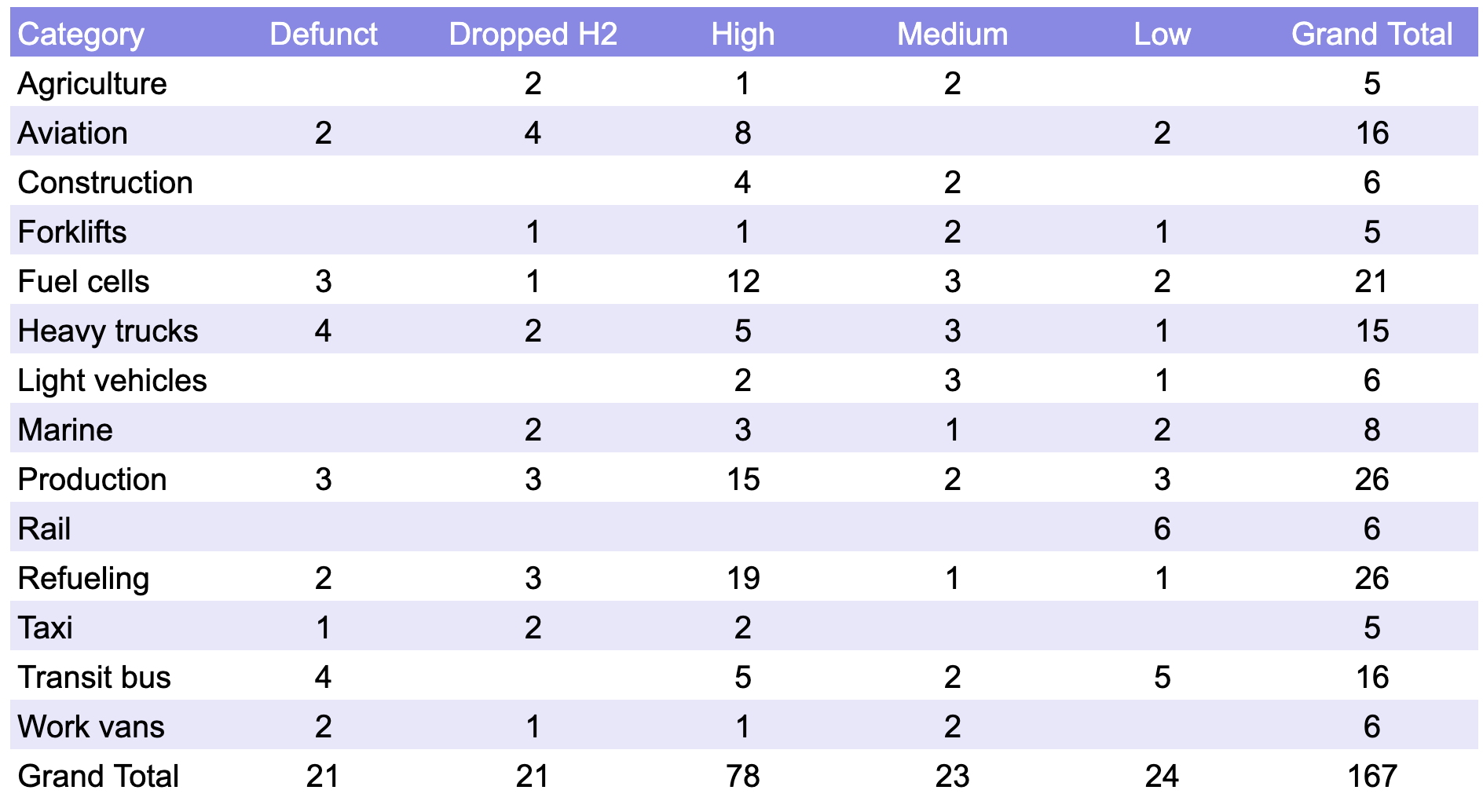

I have been tracking what I call the hydrogen transportation deathwatch this year. It is a running list of firms that have been trying to push the overcooked noodle of hydrogen into the transportation space, have been losing money for years, and now are going bankrupt or pivoting away from the space. More than a quarter of the 167 of the firms I’ve identified so far have gone bankrupt or pivoted away from hydrogen. Similarly, I’ve tracked the failures of hydrogen transportation fleets across transit bus, ferry and passenger train initiatives.

The point is not to mock the failures but to document them. The evidence is piling up that hydrogen in transportation is unraveling while battery electrics are pulling further ahead. The pace of defections is so steady that you can watch the story unwind almost in real time.

The Latourian lesson is that actor networks survive only as long as actors continue to reinforce the narrative. Black boxes are powerful tools because they allow networks to act without questioning the contents. But when enough actors open the box and find that the reality does not match the inscription, they walk away. South Korea’s police decision is one of those moments. It signals to other South Korean actors that they are free to defect too. Provinces, ministries, and companies now know that the story of hydrogen transportation is not inevitable.

This is not simply a failure of hydrogen. It is an evolution of understanding. Societies test new technologies, invest in them, and learn whether they deliver. In the case of hydrogen transportation, the lesson has become clear. The costs are too high, the infrastructure too fragile, and the alternatives too strong. Battery electrics are proving to be the practical, scalable solution. The police buses in South Korea are not just vehicles. They are markers in the larger narrative of how societies align around energy futures, and how those alignments change when reality intrudes. The hydrogen transportation deathwatch continues, and for South Korea, its national police force defecting will be remembered as one of its defining episodes.

Sign up for CleanTechnica’s Weekly Substack for Zach and Scott’s in-depth analyses and high level summaries, sign up for our daily newsletter, and follow us on Google News!

Have a tip for CleanTechnica? Want to advertise? Want to suggest a guest for our CleanTech Talk podcast? Contact us here.

Sign up for our daily newsletter for 15 new cleantech stories a day. Or sign up for our weekly one on top stories of the week if daily is too frequent.

CleanTechnica uses affiliate links. See our policy here.

CleanTechnica’s Comment Policy