Support CleanTechnica’s work through a Substack subscription or on Stripe.

Or support our Kickstarter campaign!

Equinor’s decision to halt its blue hydrogen project in Groningen is not a story about engineering failure or lack of public support. It is a story about the absence of customers. The H2M project secured support from the EU Innovation Fund and was positioned as a cornerstone of industrial decarbonization in the Netherlands. It had a defined technical pathway, a credible partner, and access to CO2 storage infrastructure in the North Sea through Northern Lights. What it did not have was industrial offtake. Without buyers willing to sign long term contracts for blue hydrogen, the project could not reach final investment decision. Markets, not rhetoric, decided the outcome.

The proposed Groningen facility was designed to produce roughly 210 to 220 thousand tons of hydrogen per year starting in the early 2030s. To put that in context, the Netherlands today consumes on the order of 0.8 to 1.2 million tons of hydrogen annually, largely for refining and ammonia production. A 220 thousand ton facility would therefore have represented roughly 18% to 27% of current Dutch hydrogen demand. Across the European Union, total hydrogen demand is approximately 8 to 10 million tons per year, meaning the Groningen project would have supplied around 2% to 3% of EU demand. Globally, where annual hydrogen use is near 95 to 100 million tons, it would have amounted to roughly 0.2%. In other words, the plant would have been significant at the national level, noticeable at the European level, and marginal in global terms, underscoring both its scale and its limits.

In context of actual end demand for hydrogen it would have loomed much larger. My projection of actual future hydrogen demand is increasingly obviously closer to right than any others, as hydrogen continues to prove expensive to make, expensive to use, outcompeted by alternatives including Fortescue’s new electrochemical green iron process that they are putting into pilot, and unnecessary in the future energy world except as a hydrogenator of biofuels. That’s certainly the perspective that we embedded into pragmatic Netherlands 2050 energy and industrial scenarios when Dutch transmission system operator Tennet engaged me to assist them in workshops with other experts in mid 2025.

The physical architecture of the project was complex and deserves to be spelled out clearly. Natural gas would have been produced offshore Norway and transported by pipeline to the Netherlands. In Groningen, that gas would have been reformed into hydrogen through autothermal reforming or steam methane reforming. The CO2 generated in that process would have been captured, compressed, conditioned to meet transport specifications, and stored temporarily on site. It would then have been shipped back to Norway and injected into offshore geological formations under the Northern Lights project. The system was a loop in which fossil carbon traveled from Norway to the Netherlands and then back to Norway. Even before debating the climate arithmetic, the supply chain required multiple transport legs, multiple compression stages, and multiple commercial interfaces.

Northern Lights itself is a CO2 transport and storage business model. It was developed by Equinor, Shell, and TotalEnergies to offer third party CO2 disposal services. It requires emitters willing to pay for capture, conditioning, shipping, and injection. In earlier analysis, I noted that Northern Lights depends on a pipeline of industrial customers committing to multi decade storage contracts. Blue hydrogen projects were expected to be anchor customers. When one of the more prominent proposed blue hydrogen projects disappears, that reduces the near term demand base for the storage system. CCS infrastructure can work technically. The question is whether emitters are willing to pay for it when partial decarbonization may not be sufficient under tightening policy regimes.

That said, blue hydrogen isn’t something I consider a high merit target for CCS. We have alternatives and as became apparent last year with a new study, the real sequestration potential is a tenth of numbers that were assumed to be correct. That means it’s a much more limited resource and has to be preserved for the highest value sequestration, that of biogenic carbon dioxide from value creating industrial processes that consume biologically sourced feedstocks. Biomethane feeding ammonia plants to replace natural gas is more likely, but more likely yet is importing green hydrogen.

Putting that aside, the legitimate industrial use case at stake here is not hydrogen for home heating or passenger vehicles. It is ammonia as a feedstock for fertilizers, explosives, and other chemicals. Global ammonia production is roughly 180 million tons per year. Most of that ammonia is made using natural gas and emits around 2.4 tons of CO2 per ton of ammonia from process emissions alone, according to the International Energy Agency. When upstream methane leakage is included on a GWP20 basis, total climate impact rises to roughly 2.7 to 3.2 tons of CO2e per ton of ammonia, depending on leakage rates between 0.5% and 1.5%. That is a large, concentrated industrial emission source with real merit as a decarbonization target.

If blue hydrogen were used to produce ammonia in Rotterdam, what would the emissions look like? Blue hydrogen from natural gas with carbon capture typically falls in the range of 1 to 4 kgCO2e per kg of hydrogen on a GWP100 basis, depending on capture rates and methane leakage. Each ton of ammonia requires 176 kg of hydrogen. At 1 kgCO2e per kg hydrogen, that translates into 0.18 tons of CO2e per ton of ammonia from the hydrogen supply. At 4 kgCO2e per kg hydrogen, it becomes 0.70 tons. Adding remaining process emissions and residual energy use, a reasonable range for blue ammonia is 0.6 to 1.8 tons of CO2e per ton on a GWP20 basis and somewhat lower on a GWP100 basis. Compared to 2.7 to 3.2 tons for grey ammonia, the avoided emissions are roughly 0.9 to 2.5 tons per ton of ammonia. That is meaningful but partial decarbonization.

An alternative pathway is manufacturing green ammonia in a high solar and wind jurisdiction such as Morocco and shipping it to Rotterdam. In that model, large scale electrolysis produces hydrogen on site at the ammonia plant. There is no methane feedstock and no CO2 capture chain. Electrolyzer capital costs outside China remain around $2,000 per kW installed. Electricity consumption is roughly 50 to 55 kWh per kg of hydrogen. If power costs $30 per MWh and electrolyzers run at 65% capacity factor, levelized hydrogen costs land in the $3.5 to $5 per kg range. Converting that hydrogen into ammonia requires the same 176 kg per ton. Shipping from Morocco to Rotterdam adds on the order of $20 to $40 per ton. The delivered green ammonia cost is plausibly $800 to $1,000 per ton in current market conditions. Operational emissions are low. Hydrogen leakage at 0.2% to 1% with a GWP20 multiplier of around 33 leads to 0.01 to 0.06 tons of CO2e per ton of ammonia. Shipping adds perhaps 0.02 to 0.04 tons. The total is 0.03 to 0.11 tons of CO2e per ton. That is near zero relative to grey ammonia.

Cost of abatement clarifies the tradeoff. If Rotterdam grey ammonia costs $600 per ton and blue ammonia costs $650, the premium is $50. If blue avoids 1.5 tons of CO2e per ton on average, the abatement cost is about $33 per ton of CO2e. If green ammonia costs $900 and avoids 2.8 tons, the abatement cost is around $107 per ton of CO2e. Blue looks cheaper per ton of CO2 avoided, but it does not reach near zero emissions. Green is more expensive today, but it approaches full decarbonization.

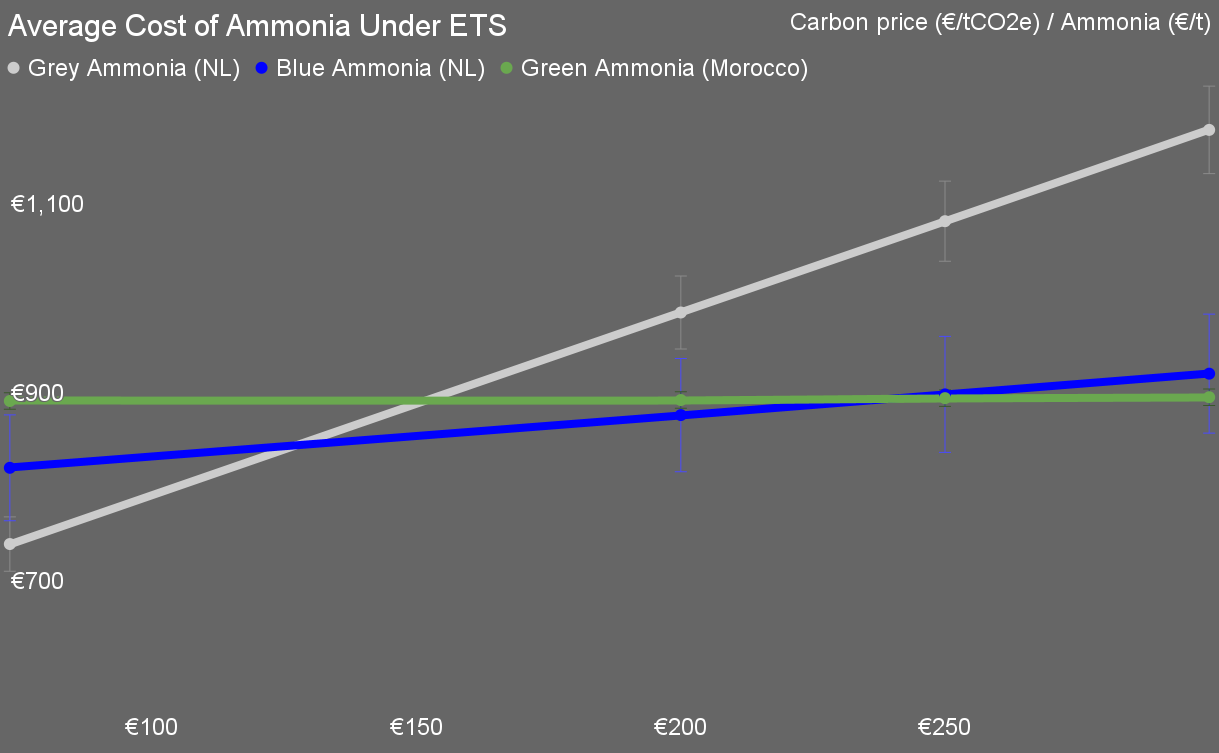

The European carbon pricing framework shifts competitiveness further. The EU ETS uses GWP100 accounting for methane and other gases. Under GWP100, methane’s multiplier is about 28 rather than over 80 under GWP20. Hydrogen’s indirect GWP100 is around 8 to 12. Carbon prices are around €73 per ton today, but EU budgetary guidance shows shadow carbon prices of €200 now, €250 in the mid 2030s, and €300 in the 2040 timeframe for alignment with climate budgets. At 10 to 12 kgCO2e per kg hydrogen, grey hydrogen faces a carbon adder of €0.73 to €0.88 per kg at €73, and €2 to €3.6 per kg at €200 to €300. Grey ammonia becomes structurally uncompetitive in a €200 to €300 world, but sees the first blue hydrogen competitive loss in the €130 carbon price range, and loses to imported green ammonia from Morocco in the €150 carbon price range.

Blue hydrogen is less exposed but not immune. At 1 kgCO2e per kg hydrogen, a €300 carbon price adds €0.30 per kg. At 4 kg, it adds €1.20 per kg. For ammonia, that is €53 to €211 per ton. If base blue hydrogen costs €3.8 per kg, then at €300 carbon it becomes €4.1 to €5 per kg.

Imported green hydrogen at €4.5 per kg with minimal carbon exposure remains around €795 per ton of ammonia for the hydrogen portion across all carbon price scenarios. Under serious carbon pricing, the contest becomes blue versus imported green, not grey versus blue.

It is important to note that ETS accounting using GWP100 is a fiscal framework, not a climate physics framework. Methane and hydrogen have stronger short term warming effects than GWP100 reflects. On a 20 year basis, methane’s multiplier is roughly three times higher. If policy were aligned with short horizon climate impacts, blue hydrogen would face a higher effective carbon cost. However, investors and industrial buyers respond to the actual ETS rules. Using GWP100, blue hydrogen appears more competitive than under a GWP20 lens, but it still carries residual carbon exposure that grows as carbon prices rise.

Why did the Groningen project fail to secure customers? Industrial buyers likely assessed long term carbon exposure, capital lock in, and regulatory risk. In a world where carbon prices are expected to reach €200 to €300, partial decarbonization that leaves 0.6 to 1.8 tons of CO2e per ton of ammonia may not be sufficient. Buyers signing 20 year offtake contracts must consider whether blue ammonia could become disadvantaged relative to near zero alternatives before the asset is fully depreciated.

In recent analysis, I argued that Germany’s hydrogen backbone was built on assumptions about ubiquitous hydrogen for energy use that never materialized, and that this misreads how industrial value chains actually operate. Germany’s pipeline infrastructure is large relative to its real industrial low-carbon hydrogen demand and in many cases lacks suppliers and offtake agreements, making it a stranded asset in waiting.

By contrast, importing green industrial intermediates such as low-carbon ammonia, green iron, or methanol from regions with abundant low-cost renewable power preserves industrial competitiveness without exposing the broader economy to volatile energy pricing or expensive under-utilized infrastructure. Importing these feedstocks allows Germany and other European producers to decarbonize upstream inputs while keeping high-value downstream transformation and manufacturing activities domestic, supporting jobs and value creation without remaking the entire energy system around hydrogen as an energy carrier rather than as a specialized industrial input. This approach treats green intermediates as tradable inputs that can be buffered, contracted, and managed commercially, rather than as system-wide energy price setters, preserving competitiveness in global markets.

The strategic objective for European industry is approaching zero emissions. Blue hydrogen can reduce emissions relative to grey. It does not remove fossil carbon from the value chain. Green ammonia produced with renewable electricity removes methane feedstock entirely and reduces emissions by over 95% relative to grey. The Groningen project was not a zero carbon solution. It was a partial one. In that context, its cancellation is not necessarily a setback. It may reflect the market signaling that incremental reductions are no longer enough in a tightening carbon budget world.

Support CleanTechnica via Kickstarter

Sign up for CleanTechnica’s Weekly Substack for Zach and Scott’s in-depth analyses and high level summaries, sign up for our daily newsletter, and follow us on Google News!

Have a tip for CleanTechnica? Want to advertise? Want to suggest a guest for our CleanTech Talk podcast? Contact us here.

Sign up for our daily newsletter for 15 new cleantech stories a day. Or sign up for our weekly one on top stories of the week if daily is too frequent.

CleanTechnica uses affiliate links. See our policy here.

CleanTechnica’s Comment Policy